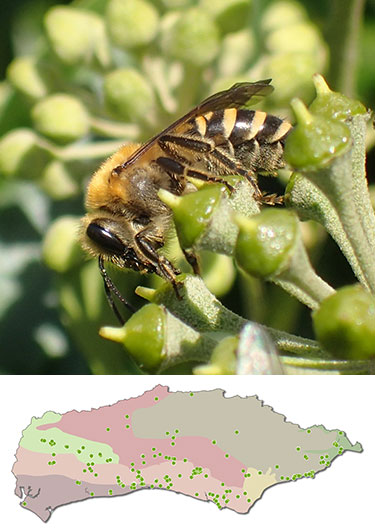

Ivy Bee (Colletes hederae) and distribution map showing widespread distribution of records in Sussex.

Photo: Chris Bentley

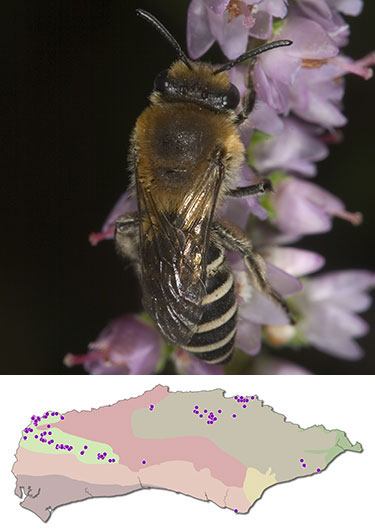

Female Heather Bee (Colletes succinctus) and distribution map showing records mainly restricted to the heathlands of north and West Sussex.

Photo: Mike Edwards

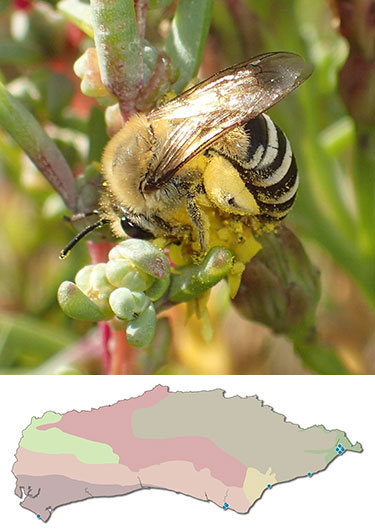

Sea Aster Bee (Colletes halophilus) and distribution map showing coastal distribution restricted to suitable saltmarsh habitats.

Photo: Chris Bentley

There are three similar species of ‘autumn Colletes’ active in Sussex at the moment: Ivy Bee (Colletes hederae), Heather Bee (Colletes succinctus) and Sea Aster (or Saltmarsh) Bee (Colletes halophilus). These species are characterised, among other things, by their late flight season (August to early November) and an orange hind margin to the first abdominal segment.

Ivy Bee was first recorded in the UK in 2001 with the first Sussex record in 2004 and it is now widespread in the county. Heather Bee and Sea Aster Bee are much more localised, with Heather Bee largely on sandy soils in the north and west and Sea Aster Bee in isolated spots along the coast where suitable saltmarsh habitat occurs.

While confident identification of species requires microscopic examination, food-plant and habitat are good pointers; large numbers of Colletes feeding on Sea Aster (Aster tripolium) on saltmarsh are almost certainly Sea Aster Bee, heather on heathy/sandy habitats Heather Bee and ivy almost anywhere Ivy Bee. However, all three species can use other food-plants and Heather Bee has apparently been recorded feeding on ivy and Ivy Bee on heather which muddles the picture somewhat, and particularly when presented with an isolated individual, it is always good to look closely at the bees themselves.

The first thing to decide is whether your bee is male or female. Males are less easy to separate, with identification often needing to be confirmed by taking a specimen and looking at it under the microscope. Males tend to be smaller and slighter than females, with more antennal segments (13 as opposed to 12 in females) though this is not easy to see in a fast moving bee! Any bee carrying pollen will be a female as only females build and stock nests.

Ivy Bee is the most easily identifiable of the three in the field and can be recognised by its large size (Honey Bee sized or bigger, larger than the other two species), broad, buff abdominal bands (orangey when fresh) and prominent buff patches on the sides of the first segment of the abdomen. The thoracic hairs are orangey-brown but this can fade with age.

The other species are very similar, with generally paler, narrower abdominal bands than Ivy Bee, whitish in Sea Aster Bee and pale buff in Heather Bee (which generally has the narrowest bands of all). Heather Bee is the smaller of the two and has black hairs among the pale hairs on the dorsal edge of the hind tibia, while those on Sea Aster Bee are completely pale (you’ll have to catch the bee and use a hand lens to see this feature).

Until you get more experienced it’s a good idea to take a LOT of photos and get into the habit (if you haven’t already) of posting them the on BWARS - Bees Wasps and Ants Recording Society Facebook page, or entering them on iRecord where experts will be able to confirm your identification (and in fact iRecord is the preferred way of submitting records).

Alternatively, send your records (ideally with photos) directly to Bob Foreman at the SxBRC.

Every month it is our aim to highlight a species that is “in-season” and, although not necessarily rare or difficult to identify, has been highlighted by our local recording groups as being somewhat under-recorded and for which new records would therefore be welcomed.

If you or your recording group are aware of species such as this then please contact Bob Foreman.