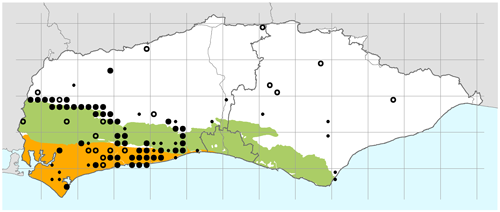

Distribution map for Arum italicum subsp neglectum

Generated from SBRS data by SxBRC

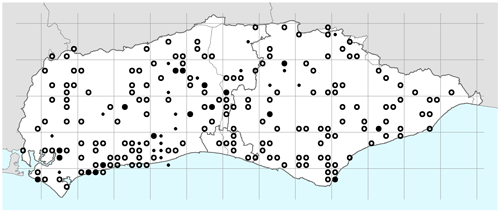

Distribution maps for Arum italicum subsp italicum

Generated from SBRS data by SxBRC

If there were a prize for the UK wild flower with the largest number of English names I’m pretty sure this one would win it... and many of its names are rather rude. It is the fault of the unapologetically upright member which wobbles within a sort of open cloak, together making up the most obvious part of the flower. The function of this arrangement is to help attract small insects so that they drop into the small chamber below where the business of pollen transfer takes place. Of course, all this happens in spring when love is in the air, with birds dating and mating, and green shoots bursting out everywhere. The ‘pint’ in Cuckoo-pint, I cannot avoid mentioning, is derived from ‘pintle’, an old nickname for the appendage of the male. But let’s try not to think about all that.

The common Lords and Ladies with pale spadix and spathe.

Photo: Nick Sturt

Form with dark spadix within an unusually dark spathe.

Photo: Nevil Hutchinson

Many plants of the common Lords and Ladies have speckled leaves.

Photo: Nevil Hutchinson

Lords-and-ladies (aka Bulls and Cows, Wake Robin, Dog’s Dibble - sorry!) is a widespread and common species in England and Ireland but north of the border in Scotland, where it does occur sparingly, it is not considered a true native. In Sussex it has been recorded in more than 94% of the 1,000 or so 2x2 km squares. Its favoured habitats include woodlands, hedge banks and other shaded areas on moist, well-drained and reasonably fertile soils; and it frequently crops up in gardens. In January and February underground tubers send up leaves which emerge rolled up and in clusters; they then unfold into a more or less arrowhead shape, often shiny green and looking as if they have had a fresh coat of gloss paint. Some plants have dark blotches on the leaves due to the pigment anthocyanin, in others the leaves are plain. The flowers appear typically in April - a tall, pale green hood-like sheath (the spathe) loosely enfolding the suggestive little ‘pestle’ or ‘clapper’ (the spadix) which may be purplish-brown or pale yellow-cream. In some individuals there is a smart dark border to the spathe and occasionally even spots. Although research has been carried out into these variations in appearance no firm conclusions have been reached as to any advantage conferred by some forms over others.

The ingenious mechanism whereby small insects are detained and presented with first the stigmas and then the stamens before being released is described in detail in Cecil Prime’s New Naturalist monograph Lords and Ladies (1960). What follows is an abbreviated account and it will help to look carefully at the excellent photograph of the flowers in cross-section kindly provided by my assistant Nevil. It has been observed that the spadix itself heats up and emits an odour attractive to flies. The scent is detectable to some humans at least, descriptions varying but united by a general theme of the bodily and the unpleasant. The surrounding spathe helps to funnel the insects into the lower chamber: they slip through a weft of one-way hairs and reach the base of the spadix where the rings of stigmas and stamens are located. Firstly they have the chance of depositing any pollen they may have gained from another Arum maculatum plant on the stigmas, which are receptive. Later, the host’s stamens present their own pollen for the insect to blunder into. After that they are free to go because by now the hairs guarding the way back up and out of the chamber have relaxed. So the escapee is free and will almost certainly fall for the same trap in another Lords and Ladies flower. Note that this mechanism is designed, through the different timing of the development of stigmas and stamens, to avoid self-pollination.

Cross-section of flowers. Arranged around the base of the spadix you can see the yellowish one-way hairs, the dark band of stamens and below them the stigmas.

Photo: Nevil Hutchinson

This is actually the ripe fruit of the Scarce species but the common one is very similar.

Photo: Nick Sturt

Emerging leaves of Scarce Lords and Ladies.

Photo: Nick Sturt

All sorts of different insects turn up for no good reason in the Arum flower but it seems that the chief pollinator, the one which falls into the trap time and time again, is the Moth- or Drain-fly Psychoda phalaenoides. After pollination the weeks pass and then in June, by which time the spathe has withered away, there is a knobbly cluster of green berries. These turn orange and are taken by birds, which in due course void the seeds away from the parent plant, so achieving the desired dispersal.

In Britain the first mention of Lords and Ladies occurs in Turner’s Herbal of 1538 as ‘Cockowpyntell’. The herbalist repeats the story found in the Greek and Roman writers that bears seek it out after waking from hibernation as it prepares their gut for the intake of food again; but he does not make any recommendations regarding its medicinal use for humans. Sussex’s own Culpeper, on the other hand, provides a long and occasionally gruesome list of its applications for just about anything from plague to freckles; but he then refuses to vouch personally for any of the cures with the wonderful disclaimer ‘Authors have left large commendations of this herb, but for my part I have neither spoken to Dr Reason nor Dr Experience about it.’

A domestic use has more authority: the boiling of the tubers to create a starch which was employed for several centuries and, apparently, much in demand in Elizabethan times for laundering ruffs. On the Isle of Portland there was a local manufactory of this product which was known as ‘Portland Sago’. Actually this industry, which died out towards the end of the 18th century, processed the tubers of a related, species, Scarce Lords and Ladies (Arum italicum subsp. neglectum). The Scarce plant is slightly larger and restricted in its distribution to the extreme south of England and Wales. In Sussex it was first recognised in 1859 by William Borrer of Henfield growing in Offington near Worthing. Its leaves emerge in November, significantly earlier than those of A. maculatum, and it can be found in West Sussex scattered over the coastal plain and also on the other side of the Downs towards the base of the scarp slope: the distribution map, based on 2x2km squares, shows this very well - the small dots indicate records from 1966 to 1999, the rings 2000 to 2015, and the amalgamation of the two into large dots records from both those periods. Should you wish to see the Scarce Lords and Ladies it is particularly plentiful along Mill Road Arundel in drifts near the Box bushes on the way to the Wildlife and Wetlands Trust reserve; Mouse Lane in Steyning is another good site. The earlier appearance of the leaves is one of the best distinguishing features: they tend to come up in scattered patches without the same rolled-up shape on emergence as the common species; the mature leaves have a more leathery texture and the veins are pale, sometimes an almost creamy colour. The Scarce Lords and Ladies also flowers later, typically in July, and the spadix - marginally chunkier - is always a pale yellow. Because of the different flowering times hybrids between A. maculatum and italicum subsp. neglectum are unusual - but not unknown and possibly overlooked.

Mature leaves of Scarce Lords and Ladies showing creamy venation.

Photo: Nick Sturt

Scarce Lords and Ladies has a chunkier spadix which is always pale.

Photo: Nick Sturt

The spectacularly veined leaves of a garden variety of Arum italicum subsp. italicum.

Photo: Nick Sturt

Finally, mention should be made of Arum italicum subsp. italicum which will be familiar to many a gardener. Over the years this native of the Mediterranean has been selected for its white leaf venation and varietal names such as pictum (‘painted’) and marmoratum (‘marbled’) have been applied. The garden plant does ‘escape’, usually as a throw-out by roadsides, and the accompanying distribution map with its random scatter of dots makes a good contrast with the concentration of dots displayed by its native relative.

Records of the common Lords and Ladies would be especially welcome when accompanied by photographs and/or notes on the degree of anthrocyanin pigmentation on leaves and spathe, and also the spadix colour. Sightings of A. italicum subsp. italicum outside of cultivation will also be appreciated and added to the dot map compiled by the Sussex Botanical Recording Society. The native subspecies neglectum does not extend into East Sussex as a native plant, though it has been found just occasionally as a presumed introduction with imported soil; otherwise its eastward distribution seems to stop abruptly at the Ordnance Survey TQ20 line.

If you want to learn more about the 2,500 or so vascular plant species which occur or have ever occurred in Sussex you are recommended to acquire a copy of the 2018 Flora of Sussex published by Pisces which is available from good bookshops or by contacting the Sussex Botanical Recording Society. The next step would be to consider joining the society itself and so enjoy recording and studying the fascinating wild flowers of our county in the company of enthusiastic and knowledgeable field botanists. We don’t often use the rude English names of plants although I can’t speak for Nevil.

Nick Sturt

Chairman Sussex Botanical Recording Society

Every month it is our aim to highlight a species that is “in-season” and, although not necessarily rare or difficult to identify, has been highlighted by our local recording groups as being somewhat under-recorded and for which new records would therefore be welcomed.

If you or your recording group are aware of species such as this then please contact Bob Foreman.