Phoretic Large Tree-chernes, Dendrochernes cyrneus (dry decaying ancient woodland), the largest British species, on an ichneumon.

Photo: © Steve F. Woodward

Reddish Two-eyed Chelifer, Roncus lubricus (woodland leaf litter).

Photo: © Gerald Legg

Moss neobisiid, Neobisium carcinoides (leaf litter, under stones).

Photo: © Gerald Legg

Knotty Shining-claw, Lamprochernes nodosus (compost and manure heaps).

Photo: © Gerald Legg

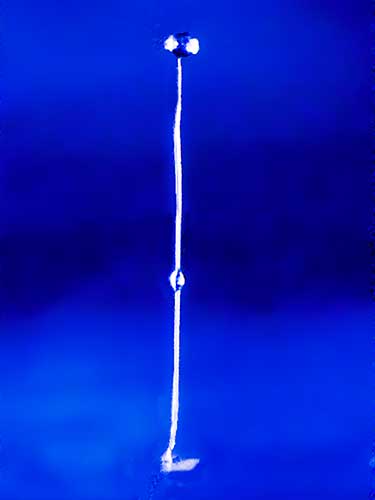

Spermatophore of the Book Pseudoscorpion, Cheiridium.

Photo: © Gerald Legg

Common Chthonid, Chthonius ischnocheles (leaf litter, under stones).

Photo: © N.A. Callow

Marram Grass Chelifer, Dactylochelifer latreillii (sand dunes, salt marshes).

Photo: © Gerald Legg

Book Pseudoscorpion, Cheiridium museorum (barns, warehouses, thatch, old libraries, hen-houses, stables).

Photo: © Gerald Legg

Miniature Tigers - False-scorpions

Miniature hunters resembling tiny scorpions, but without the sting-tipped tail, can be found in your garden living amongst dead leaves, under tree bark, in compost heaps even in old store rooms and thatch. Like spiders and harvestmen, they have eight legs making them arachnids, the fourth largest group: the Pseudoscorpions or false-scorpions. Worldwide there are over 2000 species of which 28 occur in the British Isles and Ireland. They are never large animals, the biggest species, which is an undescribed one from Pakistan, is only 15mm long.As top predators they play an important role in many habitats. Several are associated with man-made habitats and have been known for a long time, for instance the ‘Book-scorpion‘ of Aristotle, that preys on book-lice that eat parts of books. As aggressive hunters they catch their prey using their enlarged and lobster-like second pair of appendages, the pedipalps. These formidable weapons vary in shape and size depending on their favoured prey: stout strong ones for tough slow prey and thin delicate ones for fast moving thinner-skinned victims. Once caught the prey may be injected with fast-acting venom and then chewed by jaws called chelicerae as digestive juices are poured into their victim. The resulting soup is then sucked-up into the mouth.

Some species are eyeless others have either one or two pairs. These are only sensitive to light levels and cannot see detail. For a pseudoscorpion to accurately navigate, find prey and mate they feel their way using special long sensory hairs: the trichobothria, many of which occur on the pedipalps and are extremely sensitive to air movements. They also occur on the rear of the animal enabling it to know what is behind it. Other sense organs detect tiny traces of chemicals - they taste the air and surroundings.

The chelicerae of some species have a special knob or longer process on the tip of the moveable ‘finger’. This ‘galea’ produces silk that is used to make silken chambers in which the animals can moult, hibernate or look after their young. Chambers can sometimes be found beneath tree bark. Mating is dangerous, as it is in many predators, and involves keeping away from the female or seducing her, as she may think a prospective mate is potentially a nice meal. So, no direct sexual contact! Sperm are transferred to the female ‘indirectly’ and often at a distance, even in the absence of the male. He produces a short silken structure called the spermatophore that he deposits on the ground and atop of which is a packet of encysted sperm which the female picks up with her genitalia. She may randomly find one or smell it out, or be directed on to it by the male. A few species perform a mating dance like scorpions do, with the male grasping the female’s palps (neutralising them thus avoiding being eaten).

An examination of the underside of the abdomen can determine the sex of an individual, males usually having a more complex and distinctive genital area than females. The female’s genitalia are designed to pick up the sperm, store it and produce fertile eggs. Young do not have distinct genital areas. Some species fertilise their eggs soon after mating whilst others store the sperm for future use. By storing sperm these species can exploit temporary habitats like a rotting log, compost heap or birds’ nest allowing a single female with eggs and sperm to start a new population. Eggs are not laid but glued together and attached to the female's genital opening and hatch as protonymphs which also remain attached and are fed with ‘milk’ produced by the mother’s ovary. The protonymphs grow and moult into deutonymphs, then moult again into tritonymphs and finally into adults. Some protonymphs are free living others remain in the silken chamber with their mother and hence they have never been seen in the wild.

To move around they just walk, but those living in transient habitats ‘hitch-hike’ - they attach themselves to flies, beetles, parasitic wasps and harvestmen and get a lift to a new habitat which may be miles away, a process known as phoresy.

To find pseudoscorpions start by getting some woodland leaf litter, spread it out it over a white sheet or tray and wait and wait ... Pseudoscorpions defend themselves from disturbance by ‘lying low’. They will usually start to move when all the other invertebrates have run off the sheet and you have decided to start again with another load of leaves! When they do appear if you gently touch the front of them you will see a defence reaction: they have a very fast reverse gear! Once spotted make a clear, no-man’s-land area, around the individual so it can be easily tracked and use a fine lightly moistened paint brush (or a small blade of licked grass) or ‘pooter’ to pick them up. For the better equipped enthusiast pseudoscorpions can be found more efficiently using a variety of standard invertebrate techniques e.g. Tullgren funnel and D-vac (a very fine collecting bag is needed as the species are tiny; relatively cheap electric garden blowers are ideal). You can view them with a x20 hand-lens and with luck be able to identify some of the commoner species. However, it is virtually impossible to identify many without the use of a binocular microscope, and in some cases even a compound microscope may be needed. Getting the lighting right will greatly improve the chance of seeing some of the features, especially the various hairs and bristles that distinguish some species. A useful guide is produced by the Field Studies Council: Pseudoscorpions, which covers 27 species; the 28th has only (2020 in press) been recently recognised - others may still be out there to discover. You can submit images and request for help to the recording group (see www.chelifer.com) or the British Arachnological Society and there is a useful Facebook page too.

Pseudoscorpions can be searched for from February onward. When it is very cold, some species will vertically migrate down in the soil or into rotting wood etc. but when the weather is mild they are less likely to do so. The Sussex Biodiversity Record Centre has very few Pseudoscorpion records in the database and new ones would be very welcome. If you do find Pseudoscorpions, please send your records (with photos) to bobforeman@sussexwt.org.uk and they will be passed to the national recording scheme or, alternatively upload them to iRecord.

Gerald Legg

Every month it is our aim to highlight a species that is “in-season” and, although not necessarily rare or difficult to identify, has been highlighted by our local recording groups as being somewhat under-recorded and for which new records would therefore be welcomed.

If you or your recording group are aware of species such as this then please contact Bob Foreman.